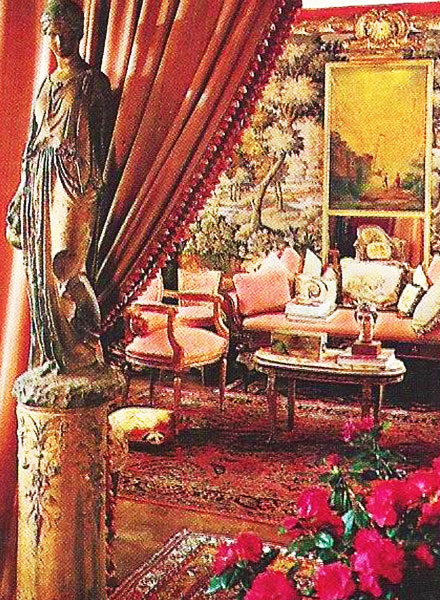

Mystery, a vital element in Adolfo’s interior design philosophy, is personified by an Italian statue guarding the entranceway to the salon.

WERE THESE ROOMS SITUATED in an hotel particulier in Paris, or in some Venetian palazzo, they would come as no surprise: damask-covered walls alternating with seventeenth-century tapestries; pillow-strewn Empire beds; floors covered with silky Oriental rugs; commodes massed with books, porcelain, odd bits of ivory. These might be the sophisticated spaces of a well-traveled nineteenth-century gentleman, or perhaps those of some romantic, bookish collector.

Adolfo

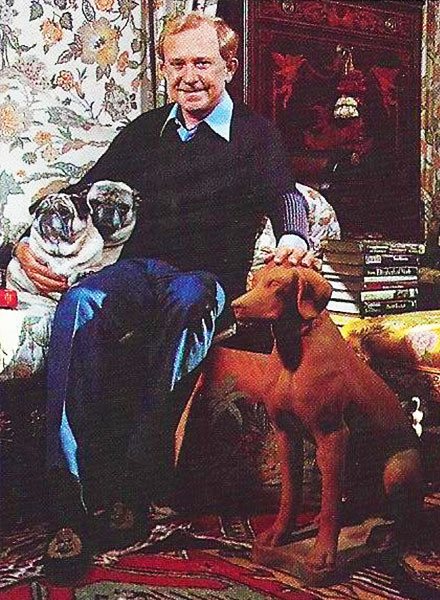

In fact, they belong to Adolfo—the gentle Cuban-born couturier who has for a number of years dressed many of the world’s most elegant women. To the cognoscenti, a classic Adolfo knit suit, for instance, is something of a piece de resistance. The designer’s apartment is his most private creation: an exotic niche in a sleek Manhattan high rise amid the upper East Side’s unforgiving corridors of glass and steel. “His home has a special warmth and elegance that surrounds you,” says his friend Gisele Masson, owner of the New York restaurant La Grenouille. “It makes you feel wonderfully lazy ” The serene intimate ambience resembles that of Adolfo’s mid-town salon, with its coromandel screens and silk-covered settees. It, too, is an anomaly in its world, for most of Adolfo’s colleagues in fashion have gone very sleek mirrored walls.

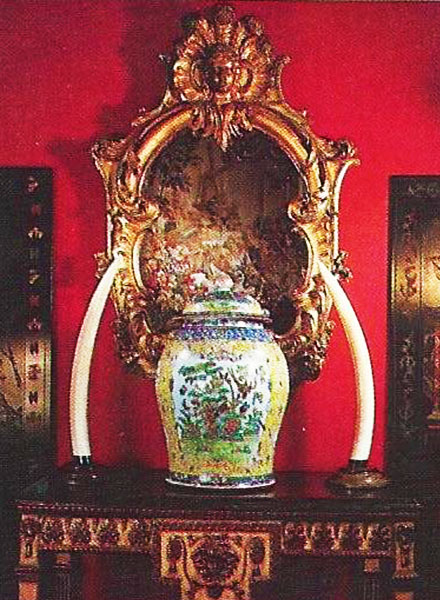

Below: In a bedroom of his Manhattan apartment, the couturier Adolfo relaxes with his two pugs and an Italian terra-cotta greyhound. below: Elephant tusks curving round a favorite Chinese jar, and a French tapestry in reflection, reveal his enthusiasm for a rich mix of objects.

Bauhaus-inspired span-ness and flannel-covered platforms. Both at home and at work the designer prefers a far more cozy and sensuous look—one that is heightened, in his apartment, by the effect of dark, lacquered walls.

“It gives a wonderful and mysterious feeling, particularly at night, which is about the only time I am home,” he says. “The living room has been painted with four coats of lacquer-red paint. “I certainly know that my taste is not everybody else’s,” he admits that may be the reason why he has never been tempted, as have other fashion designers, to design products for the home.

“The things I like suit my style of living,” he says, “and 1 would find it very difficult to put my name on designs I didn’t believe in ” Adolfo believes in following only one rule: being true to oneself.

“I don’t believe in following conventions,” he comments. ‘And the only rule that I know—for any kind of designing—is to follow intuition.”

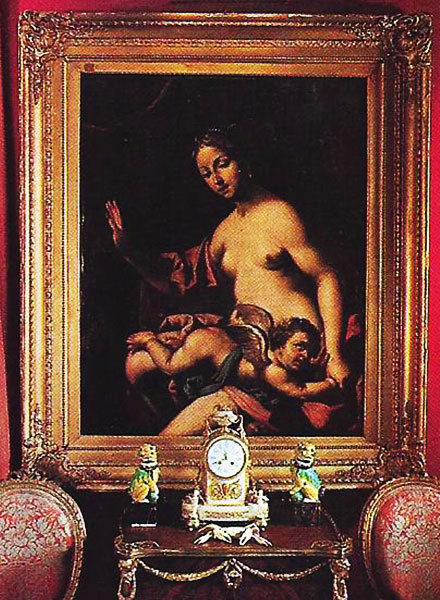

Serious art takes an amusing turn in Vouet’s Venus Spanking Amour, which accompanies an ivory crab and Chinese loo dogs in the foyer.

He is also wary of purism. “I find it far more interesting to mix—whether it’s in collecting art or in collecting clothes,” he says. In his own apartment, for instance, eighteenth-century Chinese porcelains coexist with atmospheric French landscapes, English portraits by Thomas Lawrence, and classical Italian bronze statues. His idiosyncratic attitude extends to his credo about the layout of rooms, as well. “I don’t like rooms that are limited to one kind of function,” he says, “or an ordinary bedroom-bedroom, or a living room that looks too stiff and untouchable.

I like many little rooms with different feelings, where you might sit down at any time and have coffee or tea.” Indeed, in his apartment it is difficult to tell which is the living room, because the two bedrooms actually resemble tiny libraries. Each has a sofalike Empire bed, crowded with cushions, and walls lined from floor to ceiling with shelves of books and cherished mementos, including framed photographs of the duke and duchess of Windsor, and a fanciful collage by Gloria Vanderbilt. Obviously Adolfo does not believe that “spirit of place” should necessarily influence the mood of the interior: that a modern city building, for instance, should dictate a sparse,

“I’ve always loved the eighteenth century.” —Adolfo

contemporary apartment. “If I lived in a loft in SoHo, I would feel perfectly comfortable in decorating it as I would a little Italian villa. It would all be a matter of my mood.” In his own case he has created a secretive “retreat” and the “feeling of almost being in Europe. I seem to be geared to the rooms of past centuries/’ says the designer, whose bookcases contain countless biographies of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century kings, queens and ministers of state. “And I’ve really read them all,” he says emphatically. “They’re not there just for decoration.”

The remembrance of things past is, for Adolfo, the most powerful force in decoration. “I remember, as a young man, seeing the rooms in Paris of my father’s friend Carlos de Beistegui. I always loved them; they were filled with the most wonderful antiques. And then, about the same time, seeing the rooms of eighteenth-century furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’ve always loved the eighteenth century—in a way, it was a very modern time in decoration: the feeling of space in the proportion of the rooms, and even the furniture designs. A Louis XVI chair can be very elegant and sleek and simple.” Good design, according to Adolfo, transcends centuries or periods.

It is, instead, a matter of “beautiful, perfect proportion, a certain simplicity, and of course craftsmanship, preferably by hand.” In his own apartment there is scarcely a piece of modern, machine-made furniture. The elements of lasting design are much more easily defined than another crucial factor that, to Adolfo, is quite illusive: individual style.

“Personal style is simply habit and discipline” -Adolfo ”

That’s instinctive,” he says, without a moment’s hesitation. “Personal style is something you are born with; much of it is unconscious, simply a matter of habit and discipline. “There are people with immense amounts of money who have no idea about elegance and style,” he continues. “I’ve been to houses of millionaires where rooms were filled with fake flowers. Can you imagine?” Nor does Adolfo think style in one realm—in clothes, for instance-necessarily translates to another. “They can be completely unrelated.” Taste, like style, “depends very much on the way you were raised. It’s difficult to explain, and even more difficult to learn,” he admits. But—assuming one can learn—how long does it take, and how does one learn? “It may come immediately or it may take a lifetime. With taste, also, there are no rules,” he answers. “That’s why I think interior designers are so important.

They help their clients develop a taste they might never have known they had—just as they consult a fashion designer in order to know what to wear.” Both types of designers, says Adolfo, are “messengers of taste. Each is involved in helping clients who may not have the vaguest ideas of what they want, and in showing them how to express themselves— whether with a suit or with a sofa.”